The Law of Anomalous Numbers

Published:

We have seen in previous entries how multiple statistical results allow us to find patterns in randomness. Today we talk about a strange law of numbers, Benford’s law. This is an empirical law that explains the distribution of the leading digit of observed data in real life situations. We will then draw a parallel with the law of leading digits for the powers of 2 and how can ergodic theory help us understand these phenomena.

If you like my content, consider following my linkedin page to stay updated. The code generating the plots and computing the distributions can be found in my github here.

Real life data and distribution of leading digits

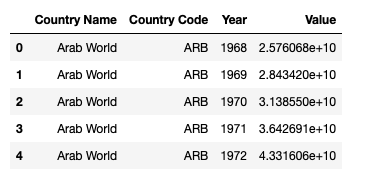

Suppose we collect data from a real life setting: in this example, we will use the nominal gdp (in US dollars) from countries. The data has been obtained from https://datahub.io/core/gdp. It consists of a list of regions and countries together with, among other indicators, their nominal gdp. We first take a look at how the table looks like:

import pandas as pd

gdp = pd.read_csv("../input/gdp.csv")

gdp.head()

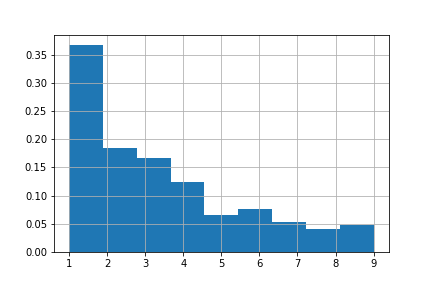

Taking a deeper look, we can see that the first rows consist of several different regions of the world. If we go low enough, we find the list of countries with several years of measurements. With some quick filtering we obtain the list of countries and their gdp in 2016. If we look at the distribution of the first digit of each of the values in the dataframe, we observe the following distribution:

We can see that the distribution has a peak at 1 and decays logarithmically. This is what Benford’s law predicts:

Benford’s law: we say that a set of numbers $S$ satisfies the Benford distribution if the frequency $f_d$ of the digit $d$ as the first digit of the numbers in $S$ is approximately

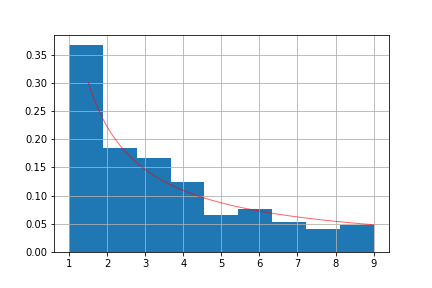

\[f_d = \log_{10}\left(1+ \dfrac{1}{d}\right)\]We plot this function along with the observed distribution from the previous plot.

We can see how the distribution of the observed data closelly follows Benford’s distribution. In general, sets of naturally ocurring numbers have been tested to follow Benford’s distribution, appearing in a mixture of context. Two heuristic conditions that seems to ensure that a given dataset follows Benford’s distribution are:

- The dataset spans over several orders of magnitude;

- The fluctuations are multiplicative.

More about these heuristics can be read in Wikipedia’s page about Benford’s law here. In particular, it has been observed to hold in several

What can ergodic theory say about this?

In previous entries (see ‘Law of large numbers, part 1’ and ‘The ergodic theorem’) we have seen several equidistribution results, for i.i.d. processes, Markov chains and ergodic processes. They all three describe the asymptotic behavior of averages of random variables: under certain conditions, the averages converge to the expected value of the random variable, almost surely. While this result is extremely powerful, we must be extremely careful with how we apply it to a real life situation. Let us see the following example:

All digits are equally likely: consider $X = [0,1]$ endowed with the Borel sigma-algebra and the Lebesgue measure. If we pick a random number from $[0,1]$, then the probability that the frequency of digits $k$ in a random number is equal to $1/10$ for all $k\in\{0,\dots,9\}$ is one. To prove this, we observe that we can define the following random variables: $X_{k,n}(\omega) = 1 \text{ if n-th digit of }\omega \text{ is } k$. This sequence of random variables is i.i.d (exercise). Note that the quantity

\[f_{k,n}(\omega) = \dfrac{1}{n}\{\text{#of k's in first n digits of }\omega\}\]is equal to the averages of $X_{k,n}$:

\[f_{k,n}(\omega) = \dfrac{X_{k,1}+\dots+X_{k,n}}{n}\]and by the Law of large numbers, this converges almost surely to the mean of the $X_{k,n}$:

\[\mathbb{E}(X_{k,n}) = \int_{0}^1 X_{k,n} dx = \dfrac{1}{10}.\]Words of caution: this does not that if we sample random numbers from $[0,1]$ we will actually observe such distribution. It does not follow from the LLN that this works for a given number.

Overcoming this issue: unique ergodicity

In the previous section we saw how even when we have almost sure asymptotic results, it is not clear if we can use this result with a given number. This is a problem which in intrinsic to almost sure convergence results: there is no way to tell if we are sampling from the zero measure set where the convergence may not be happening. To solve this, we need results with stronger convergence. It turns out that the notion of unique ergodicity is what we really need.

As in the settings of ‘The ergodic theorem’, let $(X,\mathcal{B},\mu,T)$ a probability preserving system on a compact space $X$, where the sigma-algebra is the Borel sigma-algebra. We say that the system is uniquely ergodic if $\mu$ is the unique invariant Borel measure for $T$. This implies that $\mu$ is ergodic: if it is not ergodic, there are subspaces $A,B\subset X$ with positive measure. Thus the measures

\[\mu_A(\cdot) = \dfrac{\mu(A\cap\cdot)}{\mu(A)} \quad , \quad \mu_B(\cdot) = \dfrac{\mu(B\cap\cdot)}{\mu(B)}\]are two different invariant probability measures for $T$. We also have the following characterization:

Theorem (unique ergodicity): $\mu$ is uniquely ergodic if and only if for every continuous function $f$, we have that

\[\lim_{n\to\infty}\sup_{x\in X} \left|\dfrac{1}{n}(f(x)+f\circ T(x) + \dots + f\circ T^k(x)) - \int_X fd\mu\right| = 0.\]Note that this implies that the convergences happens for all points in the space. This is particularly helpful, as we will see in the next example.

Distribution of leading digit of the powers of 2:

Benford’s law states that naturally ocurring datasets have leading digits which tend to follow Benford’s law. In this section we prove that this is actually the case for powers of 2. The proof is based on the above aproach using unique ergodicity.

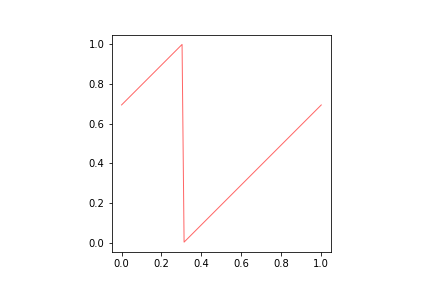

Let $X = S^1 = [0,1]/\sim$ where $\sim$ identifies $0$ and $1$, and for $\alpha$ irrational, consider the map $T\colon X\to X$ given by $T(x) = x + \alpha \pmod 1$. It is easy to see that the Lebesgue measure $m$ on $X$ is invariant under $T$ (see picture below).

We will prove that $T$ is uniquely ergodic, and that in fact, $m$ is the only invariant measure for $T$. Before the proof, we will see how this result yield the distribution law for the leading digits of the powers of 2. Let $\alpha = \log 2$ (from now to the end of the article logarithms are assumed to be in base 10). Using Stone-Weierstrass theorem one can extend the convergence in the unique ergodicity theorem to indicator functions. Assuming that the averages converge everywhere to their expected value, we can in particular take $x = 0$ and $f(x)=\chi_{[\log k , \log k +1))}(x)$. Note that if we write a given power of 2 in base 10, we have that

\[2^ n = 10^m a_m + \dots +10^0 a_0.\]Note that the leading digit of $2^n$ is then $a_m$ if and only if

\[10^m a_m \leq 2^ n \le 10^{m} (a_m+1),\]and this is equivalent to

\[m+ \log a_m \leq n\log 2 \le m + \log(a_m+1).\]If we work$\pmod {1}$ then the above inequality is equivalent to

\[\log a_m \leq n\log 2 \pmod {1} = T^n(0) \le \log(a_m+1).\]This means that the leading digit of $2^n$ is $a_m$ if and only if $T^n(0)\in [\log a_m, \log(a_m+1))$. Since the averages

\[\dfrac{1}{n}(\chi_{[\log a_m, \log(a_m+1))}(T(0))+\dots + \chi_{[\log a_m, \log(a_m+1))}(T^n(0)))\]computes how many times $a_m$ is the leading digit of $2^k$ for $k=1\dots n$, taking the limit we obtain the distribution $f_{a_m}$ of $a_m$ as leading digit, corresponding to the expected value of $\chi_{[\log a_m, \log(a_m+1))}:$

\[f_{a_m} = \lim_{n\to\infty} \dfrac{1}{n}\{\text{ #of times }a_m\text{ is the leading digit of }2^k, k=1\dots n \}= \int_0^1 \chi_{[\log a_m, \log(a_m+1))}dx = \log\left(1+\dfrac{1}{a_m}\right)\]as Benford’s distribution.

Proof of unique ergodicity

This proof is a classic example of how harmonic analysis comes to helps us proving uniformity results. We will show that any Borel probability measure $\nu$ invariant under $T$ must be equal to the Lebesgue probability measure $\mu$ on $X$. For this, we will show that they integrate the same against any continuous function $f\in\mathcal{C}(X)$.

First, we take a look at the Fourier coefficients of $\nu$:

\[\hat\nu(k) = \int_X e^{2\pi i k \theta}d\nu(\theta) = \int_X e^{2\pi i k (\theta+\alpha)}d\nu(\theta) = e^{2\pi i k\alpha}\hat\nu(k),\]where the first equality is by definition and the second by invariance of $\nu$. Since $\alpha$ is irrational, we have that $e^{2\pi i k \alpha}\neq 0$ for all $k\neq 0$, and hence $\hat\nu(k) = 0$. For $k = 0$ it is immediate that $\hat\nu(0)=1$. This implies that $\nu$ and $m$ have the same Fourier coefficients, and hence correspond to the same measure.

Final comments

In this entry we have seen how some real life datasets follow Benford’s distribution. We have also seen how ergodic theory is able to prove that a certain set of numbers (powers of 2) follow Benford’s distribution. While this does not prove that other real life sets follow the same distribution, it provides some evidence for it. We dream that there is some not know yet ergodic theoretic proof for this result, but one can only hope.

Exercise

This is an exercise from Barry Simon’s book on Harmonic Analysis: prove that the leading digits of $2^n$ and $3^n$ are asymptotically independent, that is,

\[\lim_{n\to\infty} \left(\dfrac{1}{n} \#\{ k\leq n: ld(2^n) = a_1, \ ld(3^n)= a_2\} - \dfrac{1}{n^2} \#\{ k\leq n: ld(2^n) = a_1\} \# \{ k\leq n: ld(3^n)= a_2\} \right) \to 0,\]where $ld(p)$ represents the leading digit of $p$, and $a_1,a_2\in\{1,\dots,9\}$. The hint provided by the book suggests to consider multi-dimensional irrational rotations.

Further references

Further comments on Benford’s law https://web.williams.edu/Mathematics/sjmiller/public_html/BrownClasses/197/benford/Benford_AVKontorovichSJMIller_Final06b_aa.pdf

An excellent course in Ergodic Theory https://personalpages.manchester.ac.uk/staff/charles.walkden/ergodic-theory/ergodic_theory.pdf

Leave a Comment